Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People are Dying

An urgent appeal not to look away from the crisis in Palestine and not to fall prey to passivity.

Colonizers write about flowers.

I tell you about children throwing rocks at Israeli tanks

seconds before becoming daisies.

I want to be like those poets who care about the moon.

Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons.

It’s so beautiful, the moon.

They’re so beautiful, the flowers.

I pick flowers for my dead father when I’m sad.

He watches Al Jazeera all day.

I wish Jessica would stop texting me Happy Ramadan.

I know I’m American because when I walk into a room something dies.

Metaphors about death are for poets who think ghosts care about sound.

When I die, I promise to haunt you forever.

One day, I’ll write about the flowers like we own them.

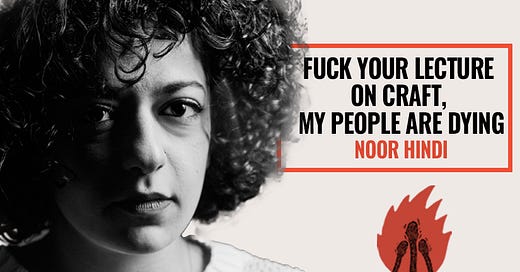

Hello and welcome to words that burn, This week’s poem is Fuck Your Lecture On Craft, My People Are Dying by Palestinian American poet Noor Hindi. It is a succinct but powerful poem. One that embraces an abrasive and urgent tone that seems more poignant now than ever.

At the time of recording, Palestine is still under assault by the state of Israel and the IDF. Every day seems to bring a fresh hell for the people of Gaza, and our feeds are filled with increasingly horrific images of acts of violence that seem unspeakable and yet keep happening. The only word for them are atrocities and they’re showing no sign of stopping.

I’ve done a number of episodes on Palestinian poets over the last few months, in an effort to highlight the culture and historical struggle of the Palestinian people. I’m including a link once again to IPSC or Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign, in the description of this episode. The IPSC does amazing work in providing relief funds and supplies for Gaza as well as organising numerous events in an attempt to raise awareness and amplify the voices of those suffering under occupation.

If you can spare anything, please consider donating to the Campaign.

In terms of amplifying voices, Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying does a phenomenal job of highlighting the plight of Palestinians, not only giving them a voice but sharpening it to a point.

This is not surprising given that Noor Hindi is a perfect modern voice for the Palestinian cause. She is a Palestinian American who writes extensively about many forms of injustice, not only the events in Palestine. The collection from which this poem is taken Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow. Each poem in the collection tackles an eclectic range of themes and topics, from the drug epidemic in the United States, to mourning, to existential crisis, Hindi turns a razor sharp eye to each and looks at them on an all-at-once microscopic and universal scale. Her unique take on such difficult topics has earned her a reputation as a unique and singular voice.

In praise of her debut poetry collection, the author Aimee Nezhukumatathil wrote:

‘’Hindi’s poems generate [a] kind of jolt… Urgent and searing, these poems are both jocular and declamatory in all the most memorable of ways— delivering crackles of energy.”(Hindi 2022)

Those crackles of energy clearly create a resonance with the reader. The true testament to this quality in Noor’s writing is the public's reaction to how she first shared the poem on Twitter, now known as X in 2020. (S. Liu, n.d.)

To call it viral is something of an understatement. The poem was shared at the height of the pandemic, when the public was particularly disillusioned with institutions and their abuses of power.

Academic Brigid Quirke provided a focused breakdown of the poems phenomenal popularity:

Off the back of an initial, much-liked Twitter post, fellow writer Rebecca Hamas tweeted a picture of the poem, attracting 5,990 retweets and more than 25,000 likes. A few months later, when Israel bombed Gaza in May 2021, further posts and reposts on Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr saw people from across the internet share, praise, critique, and discuss the poem. (Quirke 2023)

Brigid Quirke has written an incredibly in-depth essay analysing the structure, rhythm, and technical ability of the poem. I would strongly recommend you give it a read. I’ve linked it below in the description.

It’s not hard to understand this mass appeal when we experience the direct and livewire language of the poem. For the purposes of easier analysis, I’ve split the poem into three distinct sections. The first section grips the reader and refuses to let go:

Colonizers write about flowers.

I tell you about children throwing rocks at Israeli tanks

seconds before becoming daisies.

I want to be like those poets who care about the moon.

Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons.

It’s so beautiful, the moon.

That first line is a challenge to both the reader and the poetry establishment. Hindi draws a line in the sand outright in this poem: there are the colonisers and the oppressed. In this first line, too, she establishes the central, anchoring image of the poem: flowers.

Hindi’s first words are damning ones for poetry. It reaches back into the history of English poetry and references the likes of the romantics, the Victorians, and the modernists and their propensity for extolling the beauties of nature and humanity. Depicting the world as something to be praised. In this poem, that is false.

Noor decides to defy all of that with grim reality in the next two lines.

She makes it clear that she tells the truth, no matter how uncomfortable:

I tell you about children throwing rocks at Israeli tanks

The coloniser of the first line is called out directly here, and a David and Goliath narrative is established at the same time.

Then a truly morbid play on words is created. Them becoming daisies is a play on words for the English metaphor pushing daisies; a common colloquialism for dying and death.(“Be Pushing up (the) Daisies,” n.d.)

Thus, the cost of the defiance of the young is spelled out very clearly, and the juxtaposition is set in stone, Colonisers, and by proxy, the western world, can waste their time writing works of beauty, taking time to craft their work over and over, but for Palestinians, their poetry is one of the few ways to give voice to what they are forced to endure.

This in itself is a central truth of Palestinian poetry, the art form has always been used as a form of resistance since the earliest days of the Nakba (Parmenter 2010).

The speaker that Hindi creates for the poems longs for the luxury of writing about beauty , those who care about the moon but in their hearts they know they cannot be because how can you write about the liberties of the world when you are denied all of them:

Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons.

The first section that I’ve chosen ends with the phrase: it’s so beautiful, the moon. This is a deft decision by Hindi, as she ensures that we understand that Palestinians find beauty in the moon too. It prevents a reader from disengaging by saying; Well, maybe Palestinians don’t value aesthetic beauty the way we do in the west. Such a fallacy is often employed when western audiences want to dismiss a minority outright. There is a claim that we or they value different things. This is dangerous and othering rhetoric.

Otherness is the phrase coined by noted post-colonial academic Edward Said.(Said 1978). In his now famous book Orientalism, he outlined the way in which the west, primarily Europe, set about creating a fictional construct of the east, encompassing Asia as a whole. He notes the ways in which that construct was then used to justify acts of colonialism and brutality in the name of civilising the east, or, as colonists and settlers would call it, the Orient.

Academic Shehla Burney gives a excellent breakdown of Said’s insights in her own work:

The Orient was painted as the very antithesis, the binary opposition, the contrasting image of the Occident [western culture]. Colonialism and imperialism not only 'conquered' the Orient and its territory, but also its identity, (hi)story, culture, landscape, and voice.(Burney 2012)

Noor Hindi’s inclusion of that line about the moon ensures that we cannot look away, that we cannot see the politics of another region as something other. More importantly, it shows that Palestinian voices would talk about beauty if they had the luxury, but their eradication and fatal realities prevent them from doing so.

Entering the next section, Noor Hindi doubles down on Palestinians love of beauty by stating:They’re so beautiful, the flowers.

I pick flowers for my dead father when I’m sad.

He watches Al Jazeera all day.

I wish Jessica would stop texting me Happy Ramadan.

I know I’m American because when I walk into a room something dies.

Flowers continue to be the image Hindi builds her poem around, and they are once again associated with death. If the first section was a brief look at the horror of Palestinian existence for the whole country, then this section focuses heavily on the personal toll the conflict takes. Our speaker has lost their father.

It's more than just a poignant image; it's a shared experience of grief that transcends borders and conflicts. This moment in the poem reminds us that behind the statistics and news reports are real people, with real losses and moments of tender memory. It made me reflect on my own experiences of loss and how, in those moments, the simple act of remembering or holding onto something beautiful becomes a small act of resistance against the pain. Noor Hindi doesn't just share her grief; she invites us into it, asking us to see the human cost of conflict, a reminder that could make anyone's heart heavy.

This section once more touches on the concept of othering, and Hindi’s own background becomes important for understanding her poem. Her father, or presumably, his ghost, watches Al Jazeera, the international Arab news station, all day. There are two ways to interpret this line. One on the surface level, as I’ve just done, or it could be that her father spends his days glued to the news of the atrocities occurring in his native Palestine. In doing so, he is unreachable to this family, his daughter. He, like so many of us, cannot look away.

Our poet’s Palestinian American heritage comes to the fore in the next few lines. The speaker states; I wish Jessica would stop texting me Happy Ramadan. My own personal interpretation of this is that she takes this text to be a form of surface-level acknowledgement of our poets Arabic culture. In actuality, the allyship required by Palestinians cannot be some surface, token nod of recognition. More than that, the notion of being told to be happy about anything is absurd when, as the poem's title suggests, people are dying.

If our speaker knows they are Palestinian from texts from friends, their American half is confirmed in a much darker way: when I walk into a room something dies.

This is a recognition of the United States legacy when it comes to the Middle East.(Stocker 2018) It is one of blood and fire, with countless bodies littered in its wake, hence the direct metaphor employed by Hindi. In a 2020 essay, she outlined how she struggles with dual citizenship. She wrote:

The profound privilege of living in America, where a drone is a bird in the sky I look at while walking through the park. It is not a bomb, not a symbol of fear, not a cue to panic and duck. The loneliness of living in America, paying for the bombs that kill my people.(Hindi 2020)

As mentioned earlier, this poem enjoyed a high degree of virality when it was first shared by Hindi. There is little doubt that her mixed citizenship, both as a Palestinian and as an American, may play a role in this. Her writing is sharp and insightful; cutting and tender all at once. It distinctly engages in the language of the now and abandons the perceived pretension of poetry that relies too heavily on the craft. Hindi’s own experiences with Palestine make her an ideal voice for a new generation on the issue as well. The poet herself has talked about the way in which she has never actually visited Palestine but at the same time she feels the reverberation of its suffering constantly. Here, she writes about the dichotomy of that experience:

I’ve never been to Palestine though I write about it all the time…I don’t know how to wrap a keffiyeh around my neck. I don’t like hummus. I’d rather read George Abraham or Lena Khalaf Tuffaha than canonical writers like Darwish. I am still trying to reconcile my identities. My multiple displacements. The difficulty of seeing (and unseeing); the desire to be seen (and unseen). (Hindi 2020)

There are surely hundreds of thousands of people who feel a similar clash within themselves. The history of Palestine is a history of displacement, with huge swathes of Palestinians being forced to flee their homeland under threat of violence, or worse death.(Karam 2013)

Today, it’s estimated that the Palestinian diaspora is somewhere around 6 million strong (Schulz 2005). That means millions of 1st and 2nd generation immigrants who must witness the ongoing violence, perpetrated not only against their homeland but against their very identity as well.

This urgency is exactly what empowers Hindi’s voice and decrying of rigid poetic form. She understands that clarity and emotion need to be the driving force behind art—something that reaches out and grabs the reader's attention. Not something weighed down in centuries of tradition, refined from a culture that cannot understand her own.

Hindi reiterates this idea and the thesis of her poem once more in the final section:

Metaphors about death are for poets who think ghosts care about sound.

When I die, I promise to haunt you forever.

One day, I’ll write about the flowers like we own them.

Hindi’s words are searingly scornful, mocking the flowery language of other poets who experienced death a handful of times in their lives. Those who romanticise ghosts and think they care about sound. Our speaker knows that ghosts are filled with fury. She explains that when she dies, I promise to haunt you forever.

The You she is referring to is more than likely the same person trying to lecture her on craft. Those who are complicit in the violence committed against those dying, by focusing, not on the cry for help, but on whether the form it takes is valid. To me, it is reminiscent of the frustration so many of us feel as we watch international politicians pontificate on the ‘’correct’’ diplomatic solution to an attempted genocide of a people.

The ghosts of Noor Hindi’s world do not care about sound, they are not some romantic spectral vision, a jilted lover, or a caring friend. They are souls who never stood a chance against a war machine intent on wiping them out. These spectres care about justice and will haunt the world until they get it.

The final line of the poem carries an odd hope while simultaneously damning a colonial mindset again: one day I’ll write about flowers like we own them.

The speaker is all at once singular and collective, the I and we of the poem, a dream of ownership. The dream of a free Palestine. One day, Noor Hindi will be allowed to luxuriate in nature and pen poems about beauty because they will own the land they stand on once again.

Fuck your lecture on craft, my people are dying is an electric cry for aid, a klaxon for ceasefire. It is a poem that engages in decolonised thinking , beseeching the reader to see the world for what it is and not for the narrative built around it. In my opinion, it deeply resonates with those who hear it because, deep down, all will feel a sense of frustration with the trajectory of the world. Her challenge to the academic and literary world is simple; you have no right to silence or belittle the voices of others. It would be easy to classify Noor Hindi’s poem as a protest piece, but doing so would banish it to a literary category, and when we pigeonhole art like that, it allows us to think of it in one way and then dismiss it if it doesn’t fit. Hindi rages against that, mixing the personal with the political, the individual with the whole. In an interview, she stated:

A protest poem is not a protest. It's not a burning of a police building. It's not a change of legislation. But what poetry does is give voice to the people who are most impacted by violence, by colonialism, by climate disaster. …rather than somebody reporting on an event that impacts people, a poet is able to just write their own story, document their own history, and be a voice that connects to other people like them.(Sophia Liu 2023)

This poem is a connecting voice between events as they are reported and events as they actually are. It is a connecting voice for a culture under threat of erasure. Most importantly, it is a voice for a group that has been almost uncomprehendingly impacted by violence.

As I’ve already stated, Palestine is facing total eradication. The survivors of the latest wave of anti-Palestine military action undertaken by the IDF are now facing starvation and famine (Sridhar 2024). I’ve placed a link in the description to donate to the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign, a group working tirelessly to raise money for Palestinian relief.

What did you think of the poem? As always, this is my interpretation, and I’d love to hear yours. If you’d like to get in touch with me, there are a few ways to do so.

Citations:

“Be Pushing up (the) Daisies.” n.d. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/be-pushing-up-the-daisies.

Burney, Shehla. 2012. “CHAPTER ONE: Orientalism: The Making of the Other.” Counterpoints 417: 23–39.

Hindi, Noor. 2020. “Identity Politic Confessional.” Gay Mag. March 17, 2020. https://gay.medium.com/identity-politic-confessional-63178356249c.

———. 2022. Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow.

Karam, John Tofik. 2013. “On the Trail and Trial of a Palestinian Diaspora: Mapping South America in the Arab–Israeli Conflict, 1967–1972.” Journal of Latin American Studies 45 (4): 751–77.

Liu, S. n.d. “Noor Hindi, in Conversation.” Paperpile. Accessed March 5, 2024. https://paperpile.com/app/p/baac444e-4f2f-0abe-89cd-6be2f65f1ee3.

Liu, Sophia. 2023. “Noor Hindi, in Conversation.” Surging Tide. 2023. http://www.surgingtidemag.com/10/post/2022/08/noor-hindi-in-conversation.html.

Parmenter, Barbara Mckean. 2010. Giving Voice to Stones: Place and Identity in Palestinian Literature. University of Texas Press.

Quirke, Brigid. 2023. “Fuck Lectures About Sonnets: On Noor Hindi.” Cordite Poetry Review. August 31, 2023. http://cordite.org.au/essays/fuck-lectures-about-sonnets/.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Schulz, Helena Lindholm. 2005. The Palestinian Diaspora. Routledge.

Sridhar, Devi. 2024. “I Asked Public Health Colleagues about Starvation in Gaza. They Say There Is No Precedent for What Is Happening.” The Guardian, March 6, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/mar/06/colleagues-starvation-gaza-no-precedent-famine.

Stocker, James R. 2018. “20. Historical Legacies of US Policy in the Middle East.” In Chaos in the Liberal Order, 261–72. Columbia University Press.