The Words That Burn Halloween Special 2022

Poetry by Anne Sexton, Stephen Crane and Jessica Traynor to send a shiver down your spine.

Hello and welcome to this very special episode of Words that Burn, the podcast taking a closer look at poetry. It's nearly Halloween which means it's time for the podcast tradition of the Halloween special.

This year I'll be taking a look at three different poets and their sometimes sinister, quite often clever approaches to the supernatural and the eerie.

We'll start with Anne Sexton's seminal work Her Kind , a poem that invokes the witch hunts of old to reveal the still too common persecution of women today.

From there we'll hear the downright unnerving words of Stephen Crane in his poem in the desert, a Poe-esque wrestling with the self that will have you leaving the lights on.

Finally we'll finish with Jessica Traynor's poem The Witches Hex an Enemy, a collective Shakespearean cure to be used by communities. Hopefully it might inspire your own hexing work.

Each poem is unique in its treatment but at the same time sure to leave you uneasy in the dark on an October's night. So without further ado, let's begin; Here is Anne Sexton's "Her Kind":

I have gone out, a possessed witch,

haunting the black air, braver at night;

dreaming evil, I have done my hitch

over the plain houses, light by light:

lonely thing, twelve-fingered, out of mind.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

I have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the

Elves:

whining, rearranging the disaligned.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind.

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.

This became Anne Sexton's go-to poem at readings, This was the first poem she always read. Much like the theatrical language of the first stanza , she would go to great lengths to invoke a sense of drama at each recital, frequently dressing up in full costume. 1

Sexton was in every sense a confessional poet, a poet who infuses their work with sometimes overwhelming biographical detail.2 Her work frequently dealt with what she herself was going through; and in the case of Anne Sexton that was quite a lot.

Plagued by mental health issues throughout her life she was in and out of therapy for decades.3 It was a therapist who first suggested she take up writing. Those difficult experiences informed both her Poetry and her perspective.

Anne Sexton was a poet of the 1960's and a contemporary of Silvia Playh . Prior to Poetry she was a model and a housewife. These experiences led to women, particularly the role of women in society, becoming Sexton's central theme.4

In this poem she invokes the imagery of the Salem witch trials , fitting as she herself was from Massachusetts, to examine the ways in which women are portrayed both by patriarchy and sometimes themselves.

This poem is particularly preoccupied with the various aspects of women and how mercurial they can be. Each of the three stanzas focuses on one of those aspects.5

In the first stanza, she is the pure embodiment of a witch; brazen, careless wanton and, on occasion, promiscuous. Regular desires are given a sinister edge, what should be a young woman out socialising is now something "haunting the black air and dreaming evil."

The stanza is peppered with references to real witch folklore; six fingers on each hand making her "twelve fingered". 6To me this imagery of folklore is a literal marking out of the other. She is not a woman who conforms to the strict standards of 1950s America; "not quite a woman" but at the same time she recognises she is a "lonely thing."

Despite that the stanza ends with the line "I have been her kind." For me a recognition of community cloaked in a statement of otherness. There are many women in the same position.

The next stanza amps up the spooky imagery however it is simply a strange ode to the domesticity of the housewife;

have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the

elves:

The warm cave is simply a kitchen, the old fashioned language of skillets and carving regular shelves and cooking equipment. Finally the worms and elves her children. These ordinary things are given a sinister edge showing that a woman can be more than one thing; both a caring mother and a witch.

The poem itself seems to be very much an interrogation of , if not more simply a dialogue, with herself. She is hoping to reconcile the various forms of herself in her head.

The speaker states "a woman like that is misunderstood" I've taken it to mean that housewives and mothers are reduced to simple and content roles, wanting nothing more than a lovely homelife. This is what is "misunderstood" . These women want so much more.

This reading is backed by the final line refrain once more: "I have been her kind."

A lot of analysis has been done hoping to discover exactly what was meant by this and it's been found that the line is a subtle parody of the marketing rhetoric used by 1950's advertising.7

These ads would frequently implore husband's to recognise "the kind of woman" their wives were. Then they would go on to list a shallow list of virtues those wives might have and how their products reinforced those characteristics.8 Patronising to say the least. Downright insulting if we're honest.

Sexton has twisted it here creating a much more sinister community of outsiders in "her kind".

The last stanza is easily the darkest. It utilises the witch hunt imagery of old to an uncomfortable effect. We feel the humiliation of a woman stripped naked in a cage on a cart and we feel the fear and pain of flames that "still bite my thigh". The use of still is important here as it connects Sexton's contemporary 1950's witch with the witches of old. The persecution of women is alive and well in Sexton's society.

There is a real atmosphere of pressure as Sexton describes ribs cracking as the drivers wheels continue. This golden society of progress and modernity in the 50s is breaking their women. Forced conformity to their roles is taking its toll.

For me, in referencing the cage, the waving arms, the bright routes and survivor status, Sexton is referring to her own ordeals with mental health and treatment. Her struggles in that regard were well documented9 and often served as a basis for her work. She openly debauched the stigma often associated with women who had overcome such things. Cries and accusations of hysteria were not such a distant thing for many women and, once again, the refrain "I have been her kind" creates a community of these shunned/ branded women.

Her Kind is a poem of deep resonance and very personal content. Sexton uses supernatural and spooky imagery to great effect to create a shifting slinking examination of both women and herself.

From one abstract self examination to another, this time perhaps even more chilling in an indirect way. Here is Stephen Crane's In the desert:

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said, 'Is it good, friend?'

'It is bitter - bitter,' he answered;

'But I like it

Because it is bitter,

And because it is my heart.

This disturbingly poe-esque poem is in some ways typical of the type of work Stephen Crane wrote.10

Crane is an often overlooked American writer of the 1800's, one who was the subject of a massive resurgence in the 20th century. Modernists took note of his work, and critics of the 50s and 60s stated that he had "leapfrogged '' modernism altogether and ended up firmly in the territory of postmodernism.11

As a poem it is brief and evocative. It was claimed by one critic that Crane wrote poems " for the mind as opposed to the heart." Ones that linger long after they've been read.12 It's a bit ironic considering the central figure / creature here is devouring its own heart.

Calling this a poem would probably not gain us any favour with Crane himself who insisted his poetry be called "lines ". When stating the intent behind his Poetry he claimed:

‘’To give my ideas of life as a whole, as I know it.’’13

There is an element of Khalil Gibran present here; it is an almost mystic dialogue between the two subjects of the poem. Dialogues are common in Crane's lines. The speakers often used to interrogate some aspect of Crane himself, not unlike Sexton in the previous poem.

Though the physical actions in the poem may be described as Macabre, using this insight of the interrogation helps us understand some of the emotional subject at play.

The tone of the poem is quite matter of fact for a subject matter bordering on horrific, the existential, nightmarish quality tempered somewhat by a reporter's tone. This is no great shock as Crane himself worked as a war correspondent. In my own personal reading I feel that this profession is key to understanding the poem . I believe the creature devouring the heart is either eating away at sentiment , a softness for a war reporter . On the other hand because the word bitter is repeated so often I feel that perhaps Crane is trying to find some way back from his experience of war. Witnessing the horror of war must have hardened his heart significantly. As journalist Adam Gopnik says, Crane's "writing has the eerie, hyperintense credibility of remembered trauma".14

One need only read one of his field dispatches to understand why such bitterness would reside in his heart:

"The men dropped here and there like bundles. The captain of the youth’s company had been killed in an early part of the action. His body lay stretched out in the position of a tired man resting, but upon his face there was an astonished and sorrowful look, as if he thought some friend had done him an ill turn. The babbling man was grazed by a shot that made the blood stream widely down his face. He clapped both hands to his head. “Oh!” he said, and ran. Another grunted suddenly as if he had been struck by a club in the stomach. He sat down and gazed ruefully. In his eyes there was mute, indefinite reproach. Farther up the line, a man, standing behind a tree, had had his knee joint splintered by a ball. Immediately he had dropped his rifle and gripped the tree with both arms. And there he remained, clinging desperately and crying for assistance that he might withdraw his hold upon the tree."15

This is harrowing, even with its matter of fact tone.

Perhaps the naked, bestial creature is all Crane feels is left of him after these experiences.

This devouring of its own heart, a desperate attempt at remedy for that occasion. There is a hint of denial or paradox to his enjoyment of it '' I like it because it is bitter."

How could anyone like a bitter taste like that. This creature is resigned to its fate as a tired jaded creature, more animal than man, perhaps the lines are Crane's fear that he might be permanently left the same.

From witches to creatures and back again. The next poem is from Dublin poet Jessica Traynor. It once again invokes a strange community but this time to enact revenge.

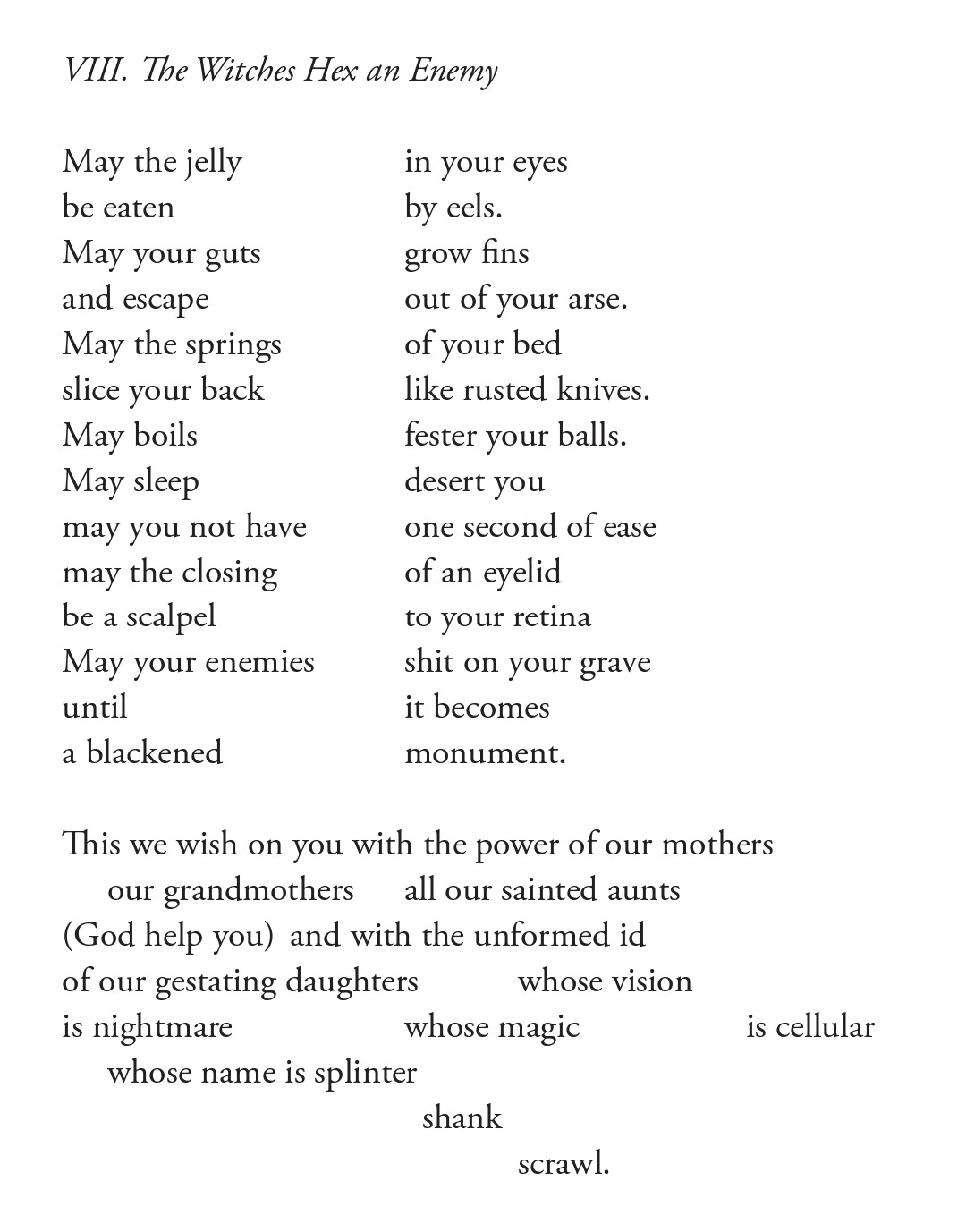

This is The Witches Hex an Enemy:

This rousing theatrical poem has all the hallmarks of Shakespearean soliloquy and would not be out of place coming out of the mouths of the weird sisters. There is the wonderful repetition of may, an exceptionally polite form of wishing malice and awful things upon another.

Of the three poems we've heard on this episode, it is arguably the most halloweeny, at least in the beginning.

The theatrical, macabre tone is a style that is very familiar for Traynor. In fact, she stated in an interview why that is:

''Not because I consider myself a particularly morbid person, but because of the imaginative scope lifting that veil can offer. Like a Victorian table-tapper, I’m more interested in creating a theatrical spectacle than imagining I have a genuine connection with the other side.''16

The more we read, the more severe the punishments become. It changes from the almost farcical tone of eels eating your eyeball jelly; so abstract in terms of its archaic language that the violence doesn't quite land to the much more wince-inducing and somehow contemporary ''may your enemies shit on your grave''. There is something increasingly dangerous to the words, shifting to something ever more aggressive.

This supreme hex forms two columns in the poem, the column on the left constantly repeats may and the targeted body part, whilst the right column delivers the wrath of the witches. This spacing causes an ominous chanting rhythm to echo up from the depths of the poem. We feel once again a truly communal aspect to this hex. It becomes a chant or even a war cry. Academic Anne Mulhall has stated that there is a new tone of ''confident feminist defiance reverberates through contemporary Irish women’s poetry''17 and cites Traynor's work as a core example. These witches refute the world of the patriarchy, perhaps certain men in particular. We know this from the mention of the ''festering balls.''

More importantly than that, this magic is cross generational. The final stanza, if that's a fair term for it, leaves the dual column format and becomes a free verse stanza. Here the origin of their magic is revealed. The use of words like sainted aunties, gives these final lines a distinctly Irish tone, combined with a well worn Irish mantra '' God Help You.'' On referencing the poems inspiration, Jessica Traynor makes it clear that these are Irish witches:

''That's what a witch is; a powerful woman in invisible shackles who has created a dark matter reactor at her core. Misogyny makes harridans of women and bullies of men. As a woman, sometimes the witches are there to save you, and other times they want to drag you down with them. Their power is seductive and they are great craic to be around. But it’s not an identity anyone would choose.''18

It's interesting that witchcraft is referred to as a double edged sword, there to ''save you'' or ''drag you down''. In those final lines there is a distinct sense that perhaps this fate of wrath and fury may be inescapable. It seems this generational hex may harness power from all, even those not yet born:

and with the unformed id

of our gestating daughters

whose vision

is nightmare

whose magic

is cellular

whose name is splinter

shank

scrawl.

There is very little positive here; whose vision is nightmare seems to echo the idea Traynor expressed that a life of magic is not an identity anyone would choose.' Perhaps Traynor hopes that future generations will not have to carry such rage in them, and will not have to call on such hexes.

Once again, the form Traynor chooses is important. The words being spaced further and further towards the end of the poem become like fragments. Mimicking the forms and sounds of the final words of the poem, splinter, shank and scrawl.

Splinter to symbolise the cellular, Shank to stand in for violence and scrawl for the words written in the hex a memory to all those women and witches.

Both of our witch poems this evening used almost playful Halloween imagery to cover much more sinister goings on, whilst our third poet employed horror as healing. It can be easy to relegate Halloween to the realm of a kitsch festival every year but to do so would be a mistake. Here in Ireland Halloween or Oíche Shamhna, was an important festival for both recognising the dead and the beginning of the darker half of the year.19 The poems we've heard in this episode do exactly the same thing. They confront the dark in the hope that insight will come from it and I hope they helped you do that too.

Happy Halloween!

Poetry Magazine. n.d. “Anne Sexton.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/anne-sexton.

Alkalay-Gut, Karen. “The Dream Life of Ms. Dog: Anne Sexton’s Revolutionary Use of Pop Culture.” College Literature 32, no. 4 (2005): 50–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25115307.

Alkalay-Gut, Karen. (2005)

POLLARD, C. (2006), Her kind: Anne Sexton, the Cold War and the idea of the housewife. Critical Quarterly, 48: 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8705.2006.00715.x

Pollard, Clare (2006)

Davies, Owen, ed. 2017. The Oxford Illustrated History of Witchcraft and Magic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pollard, Clare (2006)

Pollard, Clare (2006)

Alkalay-Gut, Karen. (2005)

Poetry Magazine and Stephen Crane. n.d. “Stephen Crane.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/stephen-crane.

Splendora, Anthony. "Book Review, Stephen Crane: A Life of Fire, by Paul Sorrentino," The Humanist, Vol. 75, No. 4 (July/August 2015), pp. 46–47

Bergon, Frank. 1975. Stephen Crane's Artistry. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03905-0.

Bergon, Frank. (1975.)

Gopnik, Adam. 2021. “The Miracle of Stephen Crane.” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/10/25/the-miracle-of-stephen-crane-red-badge-of-courage-burning-boy.

Gopnik, Adam. (2021)

RTE. 2018. “Writing The Quick: Jessica Traynor on her new poetry collection.” October 13, 2018. https://www.rte.ie/culture/2018/1010/1002298-writing-the-quick-jessica-trainor-on-her-new-poetry-collection/.

Mulhall, Anne. 2021. “Contemporary Irish Women’s Poetry, beyond the Now.” Chapter. In A History of Irish Women's Poetry, edited by Ailbhe Darcy and David Wheatley, 431–51. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108778596.026.

Dardis, Colin. 2018. “Jessica Traynor: An Interview.” The Honest Ulsterman, October, 2018. https://humag.co/features/jessica-traynor.

Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing, 2004. p. 407